Tree of the month: Zbtb7A from Mus musculus, media and gene nomenclature

First launched in Japan on February 1996, the Pokémon franchise of video-games and related media have since catched millions of fans across the globe. The original Game Boy video-games rapidly became a total hit in its motherland, a trend that continued after its release for the western public. Since then, many games of the main series, as well as dozens of spin-offs have consolidated the brand as one of the biggest video-game related intellectual properties in the world. The games are based on the concept of Pokémon or Pocket Monsters, a set of fantastic creatures with specific designs and abilities than can be collected, traded, trained and used for fighting other players. The social impact of Pokémon has not faded after all these years and proof of that are events such as parodies from the animal right activists from PETA accusing the franchise of promoting animal abuse; the internet phenomenon of “Twitch plays Pokémon”, in which thousands of simultaneous players completed the games by sending commands through a single chat; or the very recent meteoric rise of the Pokémon GO app.

First launched in Japan on February 1996, the Pokémon franchise of video-games and related media have since catched millions of fans across the globe. The original Game Boy video-games rapidly became a total hit in its motherland, a trend that continued after its release for the western public. Since then, many games of the main series, as well as dozens of spin-offs have consolidated the brand as one of the biggest video-game related intellectual properties in the world. The games are based on the concept of Pokémon or Pocket Monsters, a set of fantastic creatures with specific designs and abilities than can be collected, traded, trained and used for fighting other players. The social impact of Pokémon has not faded after all these years and proof of that are events such as parodies from the animal right activists from PETA accusing the franchise of promoting animal abuse; the internet phenomenon of “Twitch plays Pokémon”, in which thousands of simultaneous players completed the games by sending commands through a single chat; or the very recent meteoric rise of the Pokémon GO app.

As it happens often with popular pieces of media, some scientist have used the franchise to give name to their discoveries. Zbtb7A (Zinc finger and Broad complex, Tramtrack and Bric à brac A) is a gene in the POK (Poxvirus, Zinc finger and Krüppel) family of transcription factors that encode for a protein that was discovered in 2005 and named Pokemon after the franchise and as a pun with the family name. Unfortunately for the researchers that discovered and named the gene, Pokemon was identified as an oncogene, and thus deregulation of its expression was shown to be a driver factor of certain types of cancer. The combination of a popular name and the involvement in such a mediatic disease got the attention of the newspapers all over the world, that just loved to be able to announce that “Pokemon causes cancer”. This catched the attention of Nintendo, owners of the Pokémon brand, that claimed that the name of the gene was damaging to their public image. However, and despite the controversy, the name Pokemon is still widely used for this protein, probably because the name is catchy and the company cannot sue every single scientist that studies the protein.

While silly names are certainly funny and an excellent publicity for one’s research, it is a practice that has many detractors. Just like happened with the Pokemon protein, using a brand name or the name of a famous person (a fairly common practice among taxonomists) has some legal implications. Even if the naming is made as a way to show affection, the nature of the discovery may produce undesired connotations. For instance, under the point of view of an entomologist, naming a dung beetle after someone could be considered a great honor; but for people outside the field it may be considered insulting. Another community that complains about the scientific community hobby of giving silly names is the medical community. In the case of genetics, as molecular techniques are steadily being adopted in the clinical practice, the gap between academia and the patient closes, and so does the silly names that some researchers use. Doctors argue that nobody would like to hear that they are dying because, for instance, there is something wrong with their Pokemon gene. Nomenclature conventions are really confusing, and with many genes being nearly identical in function and structure between highly divergent organisms, no geneticists community is completely immune to the sin of (eventually) giving a funny name to someone’s disease. However, given that all genes have their own abbreviated code that is usually just a bunch of “innocent” letters and numbers, physicians should be able to avoid the consequences of this “disrespectful hobby”. Finally, an undesired side effect of these funny nomenclature practices could be introducing biases in research focus. After all, it is much mediatic to discover something related to a fancy named gene rather than in one with a name consisting in a boring six characters code. And while funny names are an excellent way to attract the attention of the general public, and maybe even to some students, it would be interesting to consider to what extent the success of Drosophila as a model organism has been affected by the big amount of silly gene names this organism has.

While silly names are certainly funny and an excellent publicity for one’s research, it is a practice that has many detractors. Just like happened with the Pokemon protein, using a brand name or the name of a famous person (a fairly common practice among taxonomists) has some legal implications. Even if the naming is made as a way to show affection, the nature of the discovery may produce undesired connotations. For instance, under the point of view of an entomologist, naming a dung beetle after someone could be considered a great honor; but for people outside the field it may be considered insulting. Another community that complains about the scientific community hobby of giving silly names is the medical community. In the case of genetics, as molecular techniques are steadily being adopted in the clinical practice, the gap between academia and the patient closes, and so does the silly names that some researchers use. Doctors argue that nobody would like to hear that they are dying because, for instance, there is something wrong with their Pokemon gene. Nomenclature conventions are really confusing, and with many genes being nearly identical in function and structure between highly divergent organisms, no geneticists community is completely immune to the sin of (eventually) giving a funny name to someone’s disease. However, given that all genes have their own abbreviated code that is usually just a bunch of “innocent” letters and numbers, physicians should be able to avoid the consequences of this “disrespectful hobby”. Finally, an undesired side effect of these funny nomenclature practices could be introducing biases in research focus. After all, it is much mediatic to discover something related to a fancy named gene rather than in one with a name consisting in a boring six characters code. And while funny names are an excellent way to attract the attention of the general public, and maybe even to some students, it would be interesting to consider to what extent the success of Drosophila as a model organism has been affected by the big amount of silly gene names this organism has.

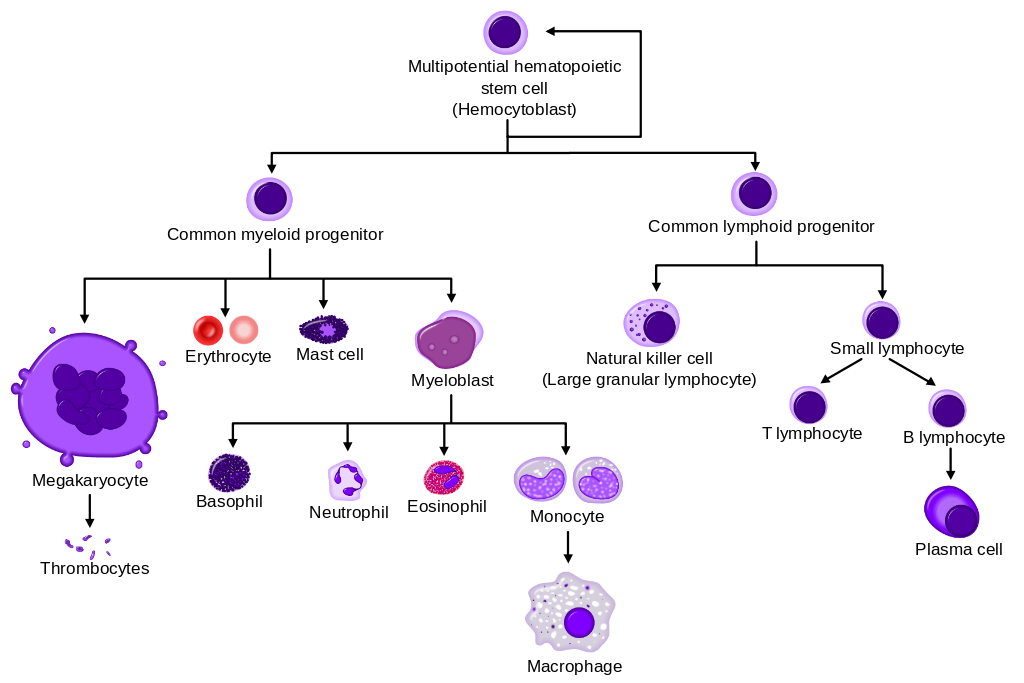

Beyond its pathological role in the development of several types of cancer, Zbtb7A is known to be highly expressed in thymus and seems to play an important role in the differentiation of the lymphoid cell line. Have this function been discovered prior to its nature as an oncogene, probably the legal problems would have never existed. The gene is also well preserved in the evolution of vertebrates, with no close relatives in invertebrates as we can observe in our tree of the month from the mouse phylome associated to the Quest for Orthologs Project.

References:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16204018

http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v438/n7070/full/438897a.html

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22500835

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23396304

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24638067

Pictures:

First picture: Twitch plays pokémon fan art, by Deviantart user hajimikimo. All rights belong to the author.

Second picture: Diagram showing the different pathways for cell differentiation during haematopoiesis, by Mikael Häggstrom. Creative Commons License.

Small picture: Koffing, one of the creatures of the game. All rights belong to Nintendo and The Pokémon Company.